Title: Corpse

Bride

What Year?:

2005

Classification:

Mashup/ Improbable Experiment

Rating:

That’s Good! (4/4)

As I write this, I’m closing in on Halloween, and have been trying to set up a lineup accordingly. Something that crossed my mind in the process is that most of my earlier pop culture memories involve animation. I can remember watching the Garfield Halloween special, the first few Simpsons Treehouse of Horror episodes, and perhaps Fantasia, all in the interval from early 1980s childhood through mid-‘90s adolescence. That convinced me that I needed an animation review somewhere in here, but I also quickly concluded that the most fitting tribute would not be among the cartoons I watched back then but something in a similar spirit. From the very short list that emerged, one quickly stood out above all others, in no small part because I had already semi-seriously considered it for other features. I present Corpse Bride, a mid-2000s stop-motion film that somehow never became the classic it deserves to be.

Our story begins in very Victorian England with a haphazardly arranged marriage between Victor and Victoria. While the pair bond in an awkward way, Victor flubs their wedding rehearsal and wanders into the woods. As he practices his wedding vows, a foully murdered woman named Emily suddenly emerges from her grave and accepts his lines as a marriage. The groom is dragged off to the strangely colorful underworld, where nobody has a problem accepting him as Emily’s husband. Meanwhile, Victoria’s scheming, near-bankrupt parents quickly make plans to marry her to a mysterious newcomer named Barkis with his own plans. Young Victor must soon make his choice- fight Barkis for Victoria’s hand, or join Emily among the dead!

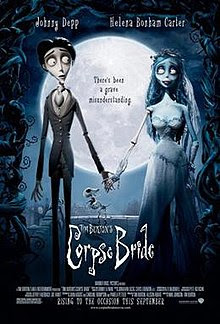

Corpse Bride was a 2005 stop-motion animated film directed by Tim Burton and Mike Johnson, reportedly based on Russian/ Slavic folklore. The animation was produced by Laika, a successor to the Will Vinton animation studio. The production employed a number of animators and crew from 1993’s The Nightmare Before Christmas, including cinematographer Pete Kozachik; director Harry Selick worked for Laika at the time but received no formal credit. A high-profile voice cast was led by Johnny Depp as Victor, Helena Bonham Carter as the Corpse Bride/ Emily, and Emily Watson as Victoria, with Albert Finney as Victoria’s father, Richard E. Grant as the villainous Barkis, and Christopher Lee (see… The Horror Express?) as the minister. The film was an unquestioned success, earning $118 million against a $40M budget, but did not receive merchandising and long-term “footprint” of Nightmare Before Christmas. Laika went on to release its first animated feature Coraline in 2009, directed by Selick. Corpse Bride remains available on disc and in digital formats.

For my personal

experiences, my frame of reference was the supernova that Coraline was

on the animation scene, and the subsequent stellar work and increasingly insulting

snubs at the Oscars (and in recent years the box office). I could have taken

any of Laika’s work for this entry, but it was Corpse Bride that stood

out as different enough for further attention. As it happens, I still came

across it by chance, after discovering it at a library sale, and watched it

soon after. To my further recollection, it was a little later when I finally

watched Nightmare Before Christmas, perhaps coloring my opinion. Even so,

I absolutely do not hesitate to call this simply the best fully stop-motion/ Claymation

feature ever made or remotely likely to be made. (I will not argue about the

difference.) It’s an actual big-budget, big-name animated feature even before Disney

made such things a relative norm, with extra support from a score by Danny Elfman

that I forgot to point out before. There are still Claymation films I can say I

“like” better, but this is the high-water mark against which everything else

must be measured.

Meanwhile, the true heart of the movie remains its depiction of the afterlife and the undead, which put it under serious consideration for the Revenant Review. Their world is pointedly more vibrant than the literal monochrome of the living, with the surely intended irony that it is the humans who look like they are in a Universal Monsters-era horror film. The dead are correspondingly uninhibited, leading to superbly realized comic possibilities when they intrude into the Victorian society above. The centerpiece is Emily (whose name is given prominently and repeatedly), yet she also serves as the clearest indicator that something is not quite right here. Behind her genuine charm, she shows the overly literal thinking and obsessive behavior commonly attributed to the undead in authentic folklore. On a deeper, darker level, she is self-centered verging into completely oblivious, repeatedly overlooking if not ignoring obvious context and circumstances, though it’s hard to avoid placing some fault on Victor for not challenging her. When Emily finally and literally dissolves (a further and powerful nod to folklore), one can be happy for her but also relieved at her departure.

That leaves the “one scene”, and I’m going with perhaps the biggest musical number. As Emily introduces Victor to her fellow undead, we meet a skeleton who leads the band of the underworld, voiced by none other than Danny Elfman himself. He tells the tale of Emily’s tragic fate with the spice and grue of an Old World ballad, in a surprisingly raspy voice (per the lore, Elfman had to quit from voice strain), accompanied by a skeletal band who use themselves and each other in place of their instruments. It’s a surreal sequence (perhaps as much so as the duel), somewhat mitigated by its obvious debt to the old-time Disney short “Skeleton Dance” among others. It is quite possibly the most definitive scene of the movie, fusing jazz with the Medieval danse macabre, setting the tone without trying to overshadow what will follow.

In closing, this is another

good movie I don’t have much more to say about. What continues to stick in my mind is that

even though I only encountered this movie quite recently in the scheme of

scenes, it “feels” like something that could and would have influenced me if I

had run across it earlier. In my own misbegotten fiction about the undead, I tried

very hard to capture some sense of authentic Slavic lore. I like to think that

in the process, I became knowledgeable enough to recognize effective use of the

source material. More than that, I find this movie accomplishes as much as I

ever set out to do, ultimately not much more or less than teaching he moral

that the living and the dead are meant to remain apart. If you want “one” movie

for Halloween, this one gets my vote, though it’s certainly not the last I’ll

be getting to. If nothing else, it’s not like anything you’ve seen or will see

again, and from me, that’s the highest compliment. And with that, I’m moving on.

No comments:

Post a Comment