Title:

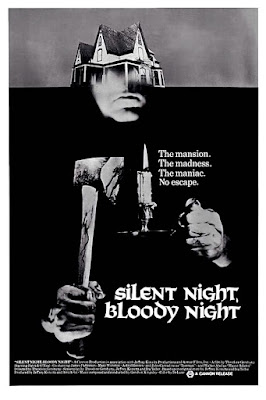

Silent Night, Bloody Night aka Night of the Full Dark Moon

What Year?:

1972

Classification:

Prototype

Rating:

For Crying Out Loud!!! (1/4)

If there’s one thing that might be surprising about my reviews, it’s that it’s not uncommon for me to start a feature for just one movie. The truly counterintuitive part is that often, the one that starts things rolling isn’t even the one I get to first. With this new feature, I have another case and point, a film that had interested me for a moderate amount of time, and it only made sense to wait for Halloween. As a bonus, it came to my attention because of an actress who has greatly impressed me through just a small part of her work. I present Silent Night, Bloody Night, a movie that has been nominated as one of the first slasher movies, and features Mary Woronov.

Our story begins with a woman narrating her life story. We then jump back in time to the gruesome death of an old man in ca 1950, which sets up a legal non-drama about the ownership of a house in the present/ early 1970s. It turns out that our narrator is Diane, the daughter of the mayor, and friendly with Jeffrey, the descendant who has inherited the house. When a couple assigned to prepare the house for sale are brutally murdered, it starts to look like the family has a darker past. That’s when we learn that the house was a mental institution before the death of the patriarch. It’s secrets and more secrets, revealed about as fast as the persons implicated end up dead anyway, all while Christmas approaches. But the real surprise is, our heroine is barely even in this movie!

Silent Night, Bloody Night was a 1972 horror film written and directed by Theodore Gershuny. The film was reportedly filmed in late 1970, and taken up for post-production distribution by Cannon Films, later the Cannon Group. (Fine, here’s the joke links.) The film featured Mary Woronov (see Terrorvision, Night of the Comet) as Diane and James Patterson as Jeffrey, with the late John Carradine as one of the victims. Woronov and several other cast members were previously best known for work with Andy Warhol. Patterson died of cancer in August 1972, several months before the film’s limited US theatrical release. The film became known as an early slasher movie and possibly the first Christmas-themed horror film, notably being released the same year as Tales From The Crypt and 2 years before Black Christmas. It gained popularity through television including annual Christmas broadcasts on certain stations, but remained poorly regarded by critics. Gershuny went on to direct several more films, including the 1973 film Sugar Cookies also featuring Woronov. The film is considered to be in the public domain based on an invalid copyright notice.

For my experiences, I have always been vocal in my disinterest in slasher movies (see Sleepaway Camp, Phenomena and for that matter High Tension). I have been coming to admit, however, that this has been largely independent of the examples I have actually watched. To me, the “best” examples I have encountered are either early enough to predate the “boom” that defined the genre or sufficiently atypical that I would put them outside it. (I’ll say this once: Texas Chainsaw Massacre is a “slasher”, Nightmare On Elm Street is not.) Beyond that, the root problem with how the genre was perceived by the 1980s is much the same as the spy movie in the 1970s (see Moonraker): By the time it reached peak popularity, the most visible examples were already either going in other directions or actually parodying the genre itself. (This is extending the benefit of a doubt to at least one 1980s “tentpole” entry.) With all that in mind, I was especially curious about this especially early artifact. After watching it, I must say that my foremost conclusion is that the “bad” elements and trends of the genre were there all along.

Moving forward, one thing I will freely admit that I made absolutely no effort to figure out this movie while I was actually watching it. On top of that, I ended up having to quit the movie and finish later, so I didn’t really view it according to my usual obsessive “rules”. I will say in my defense, however, that watching this under these non-ideal circumstances made it that much easier to notice certain flaws. First, the Christmas tie-in never goes anywhere, which really wouldn’t be a problem if the filmmaker didn’t keep trying to play it up. The bottom line on this front is that films which do this “right” can offer social commentary, actual religious symbolism or at least a sense of irony (see Night of the Comet and its predecessor Sole Survivor), which are rarely if ever in evidence here. Second, this movie is jarringly tame, to the point that I am baffled why it came out R instead of ‘70s PG (compare to, dear Logos, Tourist Trap). Even factoring in my strong suspicion that the version I viewed was censored at certain points, what we see is mild and strangely stilted. The very choice of weapons is oddly unambitious. Sure, there’s some action with an axe, but the most extensive kill sequence is strictly blunt instruments, conspicuously lacking the visceral brutality that other movies achieve with far less time and detail. The one really shocking moment comes when the damsel’s would-be rescuers meet each other with friendly fire.

Meanwhile, the central and very fundamental problem is that the movie relies far too much on its convoluted yet ultimately unambitious plot. The obvious drawback is that there’s no way in Hell the civilian viewer going to keep track of the characters and events long enough to know what they are even talking about when the biggest and most breathlessly dramatized revelations are made. (I honestly thought it was supposed to be about Diane’s own parentage, but nope…) The still deeper problem beneath that is that this film seems to misunderstand its game in ways that others did not, even at a time when everyone was still trying to settle the rules. In the most awful of the roughly contemporary giallo films (I’ll name-drop Don’t Torture A Duckling, because I know I’m never getting anything out of it), there was already enough self-awareness to understand the difference between a genre’s conceits and what is actually appealing. The identity and motives of the killer (or killers) and how it was revealed didn’t matter any more than the villain’s choice of superweapons in a Bond movie, yet this film seems to think that will be enough to impress the viewer. Worse, it still manages to make both the details and the presentation far less interesting than movies that are no better in absolutely any other respect.

That gets me far enough for the “one scene”, and I’m going with the one sequence that does something interesting enough to be memorable. Very close to the end of the movie, we get one more flashback through the diary of the patriarch. He recounts the transformation of his estate into an insane asylum, and his eventual decision to let the inmates go. He intones ominously, “I knew what they would do… but still, I let them go.” The sepia-tone flashback shows the inmates emerging to the recurring droning of a Christmas hymn, slow and, like many things here, jarringly subdued. Soon, they close in on a gathering of the wealthy donors and staff, most of whom appear too inebriated or overfed to notice as the inmates enter. What’s striking is that this is vastly more effective than the shenanigans so far. It’s heightened by the ambiguous expressions of the inmates. Some might just be confused and disoriented, others look wary and calculating, and the evident leader has a clearly focused and malign expression. Finally, he breaks a cocktail glass, while the fattest of the patrons still sleeps, and if you know giallo films, you know this isn’t going anywhere good. Per my usual refrain, this is the kind of “good” scene that makes a bad film all the more frustrating. In this case, however, I don’t think there was ever an answer except to make this the movie.

In closing, what I come

back to is the origins of the slasher genre. If one insists on having a “first”

example of the genre, at least independent of the giallo film, then this is as

good a contender as one could hope to find. It further embodies what is good,

bad and weird in film this far ahead of

the genre trends it represents. It’s so primitive and underfunded that it’s all

rough edges, yet it is also free of many/ most of the actual and alleged

cliches that would make slashers a subject of ridicule in another decade. As

usual, even the lowest rating on the scale I use here denotes a film worth

watching at least once. Just don’t expect a forgotten classic, because this is

not it. With that, I am moving on.

No comments:

Post a Comment