Title:

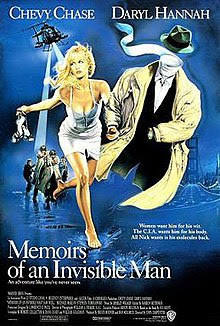

Memoirs Of An Invisible Man

What Year?: 1986

(optioning and development)/ 1992 (theatrical release)

Classification: Improbable

Experiment/ Runnerup/ Mashup

Rating: Pretty

Good! (5/5)

With this review, I’m starting yet another review feature, one which I have thought about on and off for a very long time, specifically for films which didn’t “fit” with my other features. The backstory is that when I started reviewing with Space 1979, the focus was on 1970s and ‘80s movies, with earlier and later films largely excluded. I opened up the field a lot more with the Revenant Review and Super Movies, but there were still entries piling up that I wasn’t covering, and the common denominator was 1990s films broadly in the “monster movie” genre. For a very long time, I simply planned to cover them later, ideally as another October/ Halloween run. But over the weekend, I finally got a movie that I felt forced my hand, in part because I would probably just buy it if/ when I’m ready to buy it again. In the process, I’m carrying over the Space 1979 rating scale with an “unrated” option, because what I have in mind is really all over the map. Here is Memoirs Of An Invisible Man, a team-up of John Carpenter, Sam Neill and… Chevy Chase?

Our story begins with a voice giving a monologue that hints at a longer story. As the angry narration goes on, the camera focuses on what looks like an empty chair, until a piece of gum is chewed and blown into a bubble in mid-air. We learn that our main character is Nick Halloway, a businessman who gets left behind when a vaguely described experiment that would normally done as far from civilization as possible goes awry. The end result is that Nick is left invisible, but is still detected by a group of government agents as he tries to leave the scene. Soon, he is the focus of a covert manhunt led by an agent named Jenkins. He manages to stay ahead of the agents while trying to salvage the remnants of his former life, including a romance with a lovely documentary filmmaker. But when Jenkins zeroes in on his lady love, Nick must go on the offensive to save her. Will he prevail, or has his luck run out?

Memoirs Of An Invisible Man was a Warner Bros production, officially adapted from a novel by Harry F. Saint. Its development was initiated by star Chevy Chase prior to the publication of the book, as a further effort to transition from comedy to dramatic roles; a number of further delays and departures were reportedly caused by disagreements over the tone of the film. The film was ultimately placed under the director John Carpenter, with Chase as the lead, Sam Neill as Jenkins, one year before his starring role in Jurassic Park, and Daryl Hannah of Blade Runner as the love interest Alice. Many of the film’s effects were created with CGI from Industrial Light and Magic, building on earlier work for The Abyss and Terminator 2, contributing to a final budget of up to $40 million. The movie was a commercial failure with a US box office of only $14.4M, and received many negative reviews for its handling of science fictional, dramatic and comedic elements.

For my experiences, this was a movie I was aware of when it came out, which is really looking like a bad sign. As with many things, I finally saw it on TV, and was reasonably impressed, particularly with Chase and Neill. What has interested me most is the number of genres and films it seems to reference, including a disconcerting number that came out at the same time or later. It’s clearly indebted to the Universal “Monsters” franchise, to the point of copying certain sequences and shots, and less directly to H.G. Wells, which put it on my radar during Wells-A-Thon. (I had also thought of giving this feature a head start for the ‘90s Island of Dr. Moreau.) If anything, it has an even stronger affinity with The Fugitive, actually from the following year, and the “chase” genre it inspired. The most random yet striking association that comes to my mind is InnerSpace, quite possibly the only movie to try something like this blend of elements and influences with inarguable success at the box office as well as other fronts. I find it all the more significant that this one started its difficult development about the time that film was in production.

The central reality of this movie is that, whatever Chase’s intentions, it is a comedy, albeit a fairly “dark” one. What it does show is that his obvious gifts for comedy include a command of timing, body language and situational awareness. This comes through especially in the rather odd decision to show Nick visible for most of his screen time, notwithstanding the amount of money plowed into the effects needed to make him invisible. Due credit must be given to Chase and his costars (especially Neill) that this generally works. His posture and expressions are always in character with someone who is undetected but still wary, while the rest of the cast advances the conceit by acting around him without simply looking oblivious or stupid. As the movie continues, the invisibility conceit opens up more complex and tense scenarios, as he evades the agents, eavesdrops on acquaintances, and another man’s sketchy behavior toward Alice. This is as good a point as any to mention the effects just for comparison. The transitional-period CGI easily hold up at least as well as significantly later CGI, conspicuously Hollow Man, in no small part because they don’t look that different from ‘80s practical/ optical effects. However, while the effects led to some good moment, especially a shot of Nick inhaling cigarette smoke, they are never as flat-out effective as Chevy Chase is in full view.

The natural counterpoint to chase is Neill as Jenkins. In many ways, he is the best thing about this movie, but n another level, he is the one thing that doesn’t “fit”. The impression I get on critical viewing is that the character seems written one way and played another. With Neill’s invested performance, he falls comfortably into the mold of Deputy Gerard (who was after all a character on TV first) as a “good” guy on the wrong side. But the story keeps painting him as a full-blown “black ops” agent, with a generous helping of fanaticism under the surface. On consideration, I wonder further if the filmmakers didn’t quite know what to do with him. I find this especially in their two most direct confrontations, a middle-act scene when Nick infiltrates Jenkins’ office and the finale at a construction site, The first is easily the high point of the film and for both actors (indeed very close to a choice for the “one scene”), with both stars staying fully invested in their characters and the premise. The second, in contrast, becomes a series of increasingly questionable decisions that are unnatural for either character, culminating in a conclusion so unsatisfactory I literally forgot about it until looking up the movie on disc. To me, the best reaction I can muster is my usual tendency to think of a better way to do it, but beyond writing in some common enemy to unite against, I just draw a blank.

That leaves the “one scene”, and I was considering at least two or three well after I had returned the disc I used for this viewing. My final and difficult choice is a sequence I will admit I had forgotten, portraying the aftermath of the accident which has turned not only Nick but a good part of a building invisible. The individual moments may not stand out in casual recollection, but the surreal whole gives its own impression. It is easily the most compelling effects sequence in a film that often works at least as well without them. The structure looks like it is in ruins yet still standing, with furniture, walls, rooms and whole sections seemingly suspended in mid-air. As Nick and the investigating agents try to make their way through the building, they repeatedly run into walls and obstacles that are now invisible. In the process, the invisible man disturbs enough still-visible objects for the agents to realize his existence for the first time. (The state of his clothes will be a matter of recurring inconsistencies.) The tension rises as they close in, but the true culmination is when the structure finally disappears in full, either wholly disintegrated or else transmuted to another plane of existence.

In conclusion, I will

acknowledge that this is a movie I have rated higher than it deserves (about on

par with Dr. Moreau). There’s enough problems that I could have taken it

down a rating. But when these issues are balanced against the effort and talent

clearly invested, not to mention the disastrous misfortunes that afflicted the

project, these are minor complaints at most. This is a movie that’s overdue for

recognition as what it is: A clever, creative adventure that took moviemaking

in new directions. It might not be “great”, then or now, but it gets a pass

from me.

No comments:

Post a Comment